|

Arbeitsgruppe für Theoretische Chemie |

Deutsch | Search |

| TU Dresden » Bereiche » Mathematik und Naturwissenschaften » Chemie und Lebensmittelchemie » Physikalische Chemie » Theoretische Chemie |

NAVIGATION

Start

Start

Research

Research

Group members

Group members

Location

Location

Job vacancies

Job vacancies

Publications

Publications

Internal information

Internal information

TEACHING

News

News

Lectures & Exercises

Lectures & Exercises

Lab Courses

Lab Courses

Miscellanea

Miscellanea

Research

We develop computational tools for describing chemical and physical phenomena at an atomistic level. We apply these methods in the investigation of advanced materials in order to complement experimental data which is often unavailable or incomplete. Computational chemistry is an interdisciplinary science, which combines chemistry, physics, biology, materials science, and nanotechnology.

Research activities in detail

- Methods Development

- Ultrathin Materials

- MOFs and SURMOFs

- Proton-transfer reactions in soft matter

- Hydrogen storage in graphene-based nanostructures

- Metal-organic frameworks

- DFT investigations of magnetic properties in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)

- MoS2 Nanotubes and Layers

- Optical and electronic properties of molybdenum disulfide monolayers

- Properties of boron-rich systems

Methods Development

| |||||||||

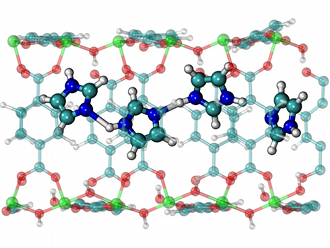

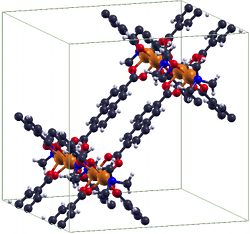

MOFs and SURMOFs

MOFs and SURMOFs are crystalline porous materials composed of two components: metal or metal oxide moieties and organic molecules known as linkers. The MOFs can be synthesized via reticular chemistry. The choice of metal and linker has significant effects on the structure and properties of the particular MOF. MOFs have broad applications because of two key attributes: their extremely large surface area and the large variety of structure and functionality of their constituting building blocks. MOF applications include gas storage, gas separation, quantum sieving, catalysis, sensors, proton and electric conductivity etc. Using the available arsenal of computational methods (electronic structure methods and classical FF methods) our research on MOFs and SURMOFs is focused on:

| |||||||||

Ultrathin MaterialsUltrathin materials are extremely interesting as building blocks of next-generation nanoelectronic devices because it is much easier to fabricate circuits and other complex structures by tailoring 2D layers into desired forms. Due to their atomic scale thickness and extraordinary electronic properties, 2D materials are the ultimate limit of miniaturization in the vertical dimension and allow shorter transistors before short channel effects set in. | |||||||||

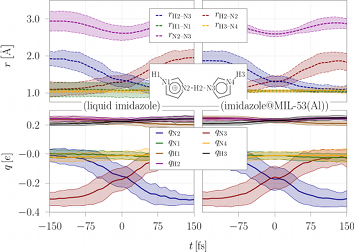

Proton-transfer reactions in soft matterProton-transfer reactions and mechanisms are essential in technological processes, e.g. in proton-exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs).

The fuel cell membrane is responsible for the transport of protons between the electrodes. Different membrane materials are used to date,

of which Nafion is the most common one. However, the proton transport in Nafion membranes critically depends on the water content,

which limits the operating temperature to the boiling point of water. References(1) E. Eisbein, J.-O. Joswig, G. Seifert, J. Phys. Chem. C 118 (2014) 13035-13041.(2) W. L. Cavalcanti, D. F. Portaluppi, J.-O. Joswig, J. Chem. Phys. 133 (2010) 104703/1-6. (3) J.-O. Joswig, G. Seifert, J. Phys. Chem. B 113 (2009) 8475-8480. (4) J.-O. Joswig, S. Hazebroucq, and G. Seifert, J. Mol. Struc.: THEOCHEM 816 (2007) 119-123. Contact: Dr. Jan-Ole Joswig | |||||||||

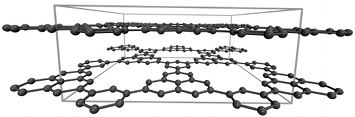

Hydrogen storage in graphene-based nanostructuresHydrogen storage by physisorption in graphene-based nanostructures is certainly comparable to the performance of state-of-art "reference" materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [their uptake normally does not exceed ~7 wt% at 77 K]. As a result, graphene-based materials represent a practical alternative to MOFs which are (in many cases) humidity-sensitive (i.e., subject to hydrolysis) and very expensive. Our recent focus has been on computational studies (classical Grand canonical Monte Carlo) in multilayered graphene systems with defect-induced additional porosity. We considered model systems which consist of infinite parallel graphene layers with "holes" of different sizes (~6-30 Å). We found that the incorporation of defects (preferably small "holes", up to 10 Å in diameter, cf. Figure 1) results in the increase of theoretically possible surface areas beyond the limits of ideal defect-free graphene (~2700 m2/g) with the values approaching ~5000 m2/g. This leads to promising hydrogen storage capacities of up to 6.5 wt% at 77 K (15 bar). Modelling was supported by an experimental work performed in the group of Dr. Talyzin (Umeå University, Sweden). References(1) I.A. Baburin, A. Klechikov, G. Mercier, A. Talyzin, G. Seifert, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy. 2015. Vol. 40 (2015) 6594-6599 | |||||||||

Metal-organic frameworksIn recent years the group of Prof. Seifert has gained a wide experience in simulating the properties of porous solids, mainly metal-organic and covalent organic frameworks as well as porous carbons. This experience involves the calculation of gas adsorption isotherms by classical GCMC methods, identification of adsorption sites by molecular dynamics simulations at the DFTB (density-functional based tight binding) level of theory and the flexibility ("breathing") of metal-organic frameworks based on ab initio molecular dynamics. Furthermore, there is a strong expertise in topological modeling of not-yet-synthesized structures applied to zeolitic imidazolate-based frameworks (ZIFs, cf. Fig. 1). References(1) I.A. Baburin, B. Assfour, G. Seifert, S. Leoni, Dalton Trans. Vol. 40 (2011) 3796-3798(2) H. C. Hoffmann, B. Assfour, F. Epperlein, N. Klein, S. Paasch, I. Senkovska, S. Kaskel, G. Seifert and E. Brunner, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (2011) 8681-8690 (3) B. Assfour, S. Leoni, G. Seifert, J. Phys. Chem. C. 114 (2010) 13381-13384 (4) E. Eisbein, J.-O. Joswig, G. Seifert, J. Phys. Chem. C. 118 (2014) 13035-13041 | |||||||||

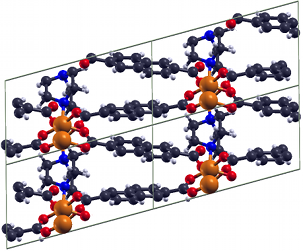

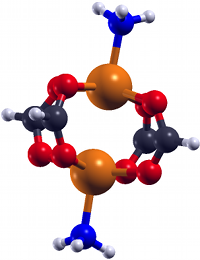

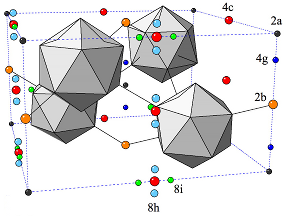

DFT investigations of magnetic properties in metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)Metal organic frameworks (MOFs) gained very high interest over the last decade due to their high

porosity, low density and absorption behaviour. Some MOFs exhibit transition metal centers,

which can lead to a certain magnetic ground state within the system. In order to investigate

the magnetic ground state of e.g. the exible MOF DUT-8(Ni) [1,2], ab initio investigations in the

framework of density functional theory (DFT) have been carried out. This MOF exists in two

crystalline structures (DUT-8(Ni)open /DUT-8(Ni)closed), where both of them exhibit low-spin

states, thus an antiparallel alignment of the spins at the magnetic centers.

Further investigations included several model systems. Those models consist of the two magnetic centers and their chemical environment. Different alterations of this chemical environment were introduced to see the corresponding change in the magnetic behaviour. This allows an insight into what could happen to the crystalline systems if such changes were implied into the periodic structures. Some alterations to the model systems, especially the ones including a removal of the NH3 groups, show that the ground changes from low-spin to high-spin. This provides a starting point for further investigations which might lead to a stable high-spin MOF. Another interesting research field is the structural determination of MOFs using NMR. A favourable canditate for NMR is 129Xe as it is mononuclear, chemically inert and has a spin of I = 1/2. Experiments are carried out for the MOFs UiO-66 and UiO-67, which are Zr based structures. The corresponding NMR parameters for the chemical shift of Xe δXe inside such structures can be determined by means of DFT. This can help to understand the experimental spectrum and to predict trends of δXe for different conditions. References(1) V. Bon et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17 (2015) 17471-17479(2) K. Trepte, S. Schwalbe, G. Seifert, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17 (2015) 17122-17129 | |||||||||

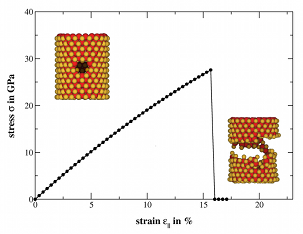

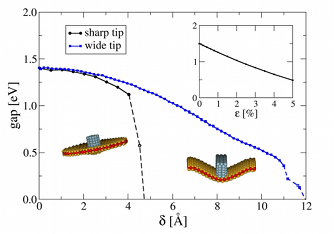

MoS2 Nanotubes and LayersSince their discovery in the early 90s of the 20th century, inorganic nanomaterials are of great interest due to their attractive electronic, mechanical, optical and magnetic properties. For that reason we investigate these properties theoretically using amongst others the DFTB method especially for MoS2 nanomaterials. Bulk MoS2 is an indirect semiconductor whose band gap becomes direct due to quantum confinement, when monolayer MoS2 is fabricated by separating single layers from the bulk material. The semiconducting nature is a big advantage offering the opportunity of, e.g., constructing transistors with low power dissipation. Additionally, due to their robust mechanical behaviour monolayer MoS2 could be suitable for a variety of applications such as reinforcing elements in composites and for fabrication of flexible electronic devices. To get a better understanding how these materials and their properties behave under specific conditions and how they could be influenced and utilised for different applications, we have performed molecular dynamics simulations to investigate the mechanical stability and resistance, as well as the breaking behaviour of MoS2 nanotubes and layers. Furthermore, we analysed the change of the electronic structure during these structural deformations and introduced local structural defects caused by missing atoms to get an idea of the size of their influence on the mentioned properties.References(1) T. Lorenz, D. Teich, J.-O. Joswig, G. Seifert, J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (2012) 11714-21(2) T. Lorenz, J.-O. Joswig, G. Seifert, 2D Mater. 1 (2014) 011007 (3) T. Lorenz, M. Ghorbani-Asl, J.-O. Joswig, T. Heine, G. Seifert, Nanotechnology 25 (2014) 445201 (4) J.-O. Joswig, T. Lorenz, T. B. Wendumu, S. Gemming, G. Seifert, Acc. Chem. Res. 48 (2015) 48-55 Contact: Dr. Jan-Ole Joswig | |||||||||

Properties of boron-rich systemsThe electron-deficient element boron represents a challenge to both experiment and theory. The list of unknowns and questions is long: How can we understand the chemical bonding? Why are boron-rich crystal structures so complex? How many elemental phases exist? What is the ground state structure? How does the phase diagram look like? Are there non-icosahedral nanostructures? etc.

Our main objective is to tackle these questions by theoretically studying structural, chemical and physical properties of boron bulk and nanostructures. Recent results focused on boron sheets, boron nanotubes and α-tetragonal boron. We are closely collaborating with experimentally working partners and also organize an annual, international boron symposium within the

MS&T conference.

References(1) J. Kunstmann, V. Bezugly, H. Rabbel, M. H. Rümmeli, G. Cuniberti, Advanced Functional Materials 24 (2014) 4127(2) I. G. Gonzalez-Martinez, S. Gorantla, A. Bachmatiuk, V. Bezugly, J. Zhao, T. Gemming, J. Kunstmann, J. Eckert, G. Cuniberti, M. H. Rümmeli, Nano Letters 14 (2014) 799 (3) V. Bezugly, J. Kunstmann, B. Grundkötter-Stock, T. Frauenheim, T. Niehaus, G. Cuniberti, ACS Nano 5 (2011) 4997 (2011) | |||||||||

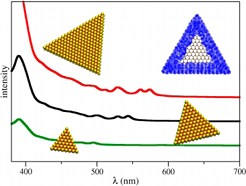

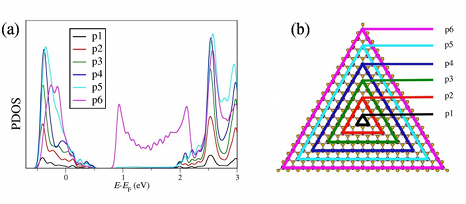

Optical and electronic properties of molybdenum disulfide monolayersMolybdenum disulfide (MoS2) is a compound among the rich family of layered transition-metal

dichalcogenides that has been studied most intensively in the past 40 years. Whereas bulk MoS2

is a semiconductor with an indirect band gap of 1.3 eV, monolayer MoS2 is a direct-gap

semiconductor with a band gap of 1.8 eV. Monolayer MoS2 has been used to build transistors

with very promising electron mobility. Furthermore, MoS2 has been recently exploited for

biosensing and energy-storage applications, and strong absorption and photoluminescence bands

were observed in the visible range at 1.9 eV (~650 nm).

References(1) T.B. Wendumu, G. Seifert, T. Lorenz, J.-O Joswig and AN Enyashin, J. Phys.Chem. Lett 5(21) (2014) 3636-3640(2) J.-O Joswig, T. Lorenz, T.B. Wendumu, S. Gemming, G. Seifert, Acc. Chem. Res. 48 (2015) 48-55 | |||||||||

CONTACT

Secretary

Antje Völkel

Tel.: +49 (0) 351 463 34467

E-Mail: Antje.Voelkel (at) tu-dresden.de

Location

Bergstraße 66c

König-Bau

Raum 106a

Postal Address

TU Dresden

Fakultät Chemie und Lebensmittelchemie

Professur für Theoretische Chemie

01062 Dresden

Parcels & Deliveries

TU Dresden

FakultätChemie und Lebensmittelchemie

Professur für Theoretische Chemie

Bergstraße 66c

01062 Dresden